Sint Benedictus Mortsel

Mortsel , "a city ahead" , has an obvious and mild form of urbanization.

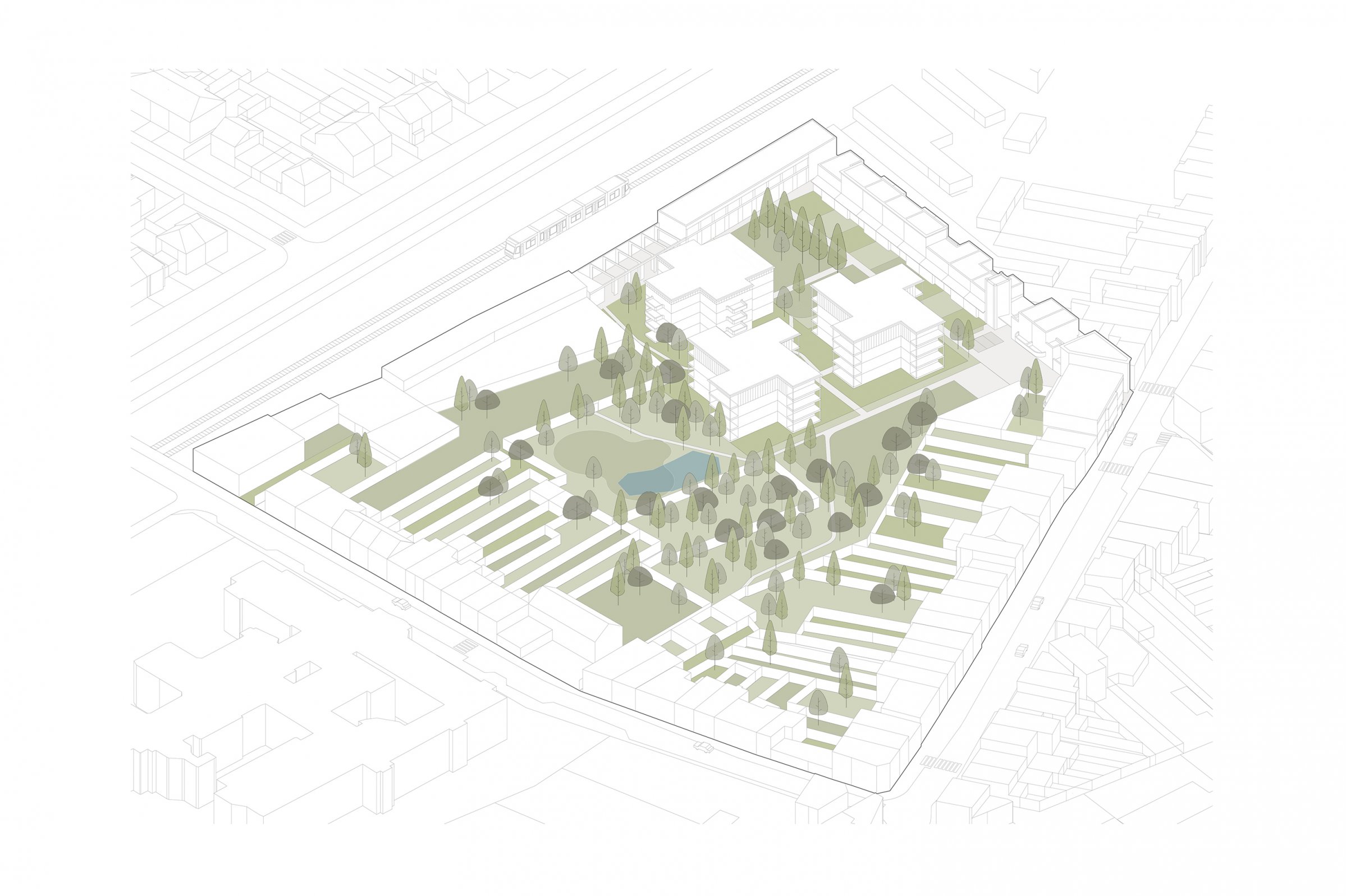

As the closest suburb of Antwerp, the first city outside the City, it is increasingly becoming an attractive residential environment with a clear identity, which is growing steadily. In the 19th century, new, larger structures were laid over the original rural structure of church and castle, of heir road and causeway: railroads cut into the city, forts defined large voids in the urban fabric and the R11 cut across existing roads and paths. In the 20th century, the fragments of the finely woven fabric that remained were further developed with residential extensions, often relatively dense.

The perimeter blocks here become thinner and larger, eventually atomizing into allotments. The potential for growth in Mortsel is concealed in "outdoor rooms" that are often hidden behind ribbons of small row houses or villas or sometimes part of a larger logic. Here a kind of city within the city emerges, with much more recent and usually larger-scale developments and infill projects nestling in the available pit of the original building blocks. There is also a certain danger in this accretion: the leaps of scale produce all sorts of conflicts between private and public, between the original scale of habitation and these new small campuses in the original fabric.

Residential project with dwellings & social housing

around a collective garden

Closed competition, Open Call

Mortsel-Belgium

2021

In the pocket

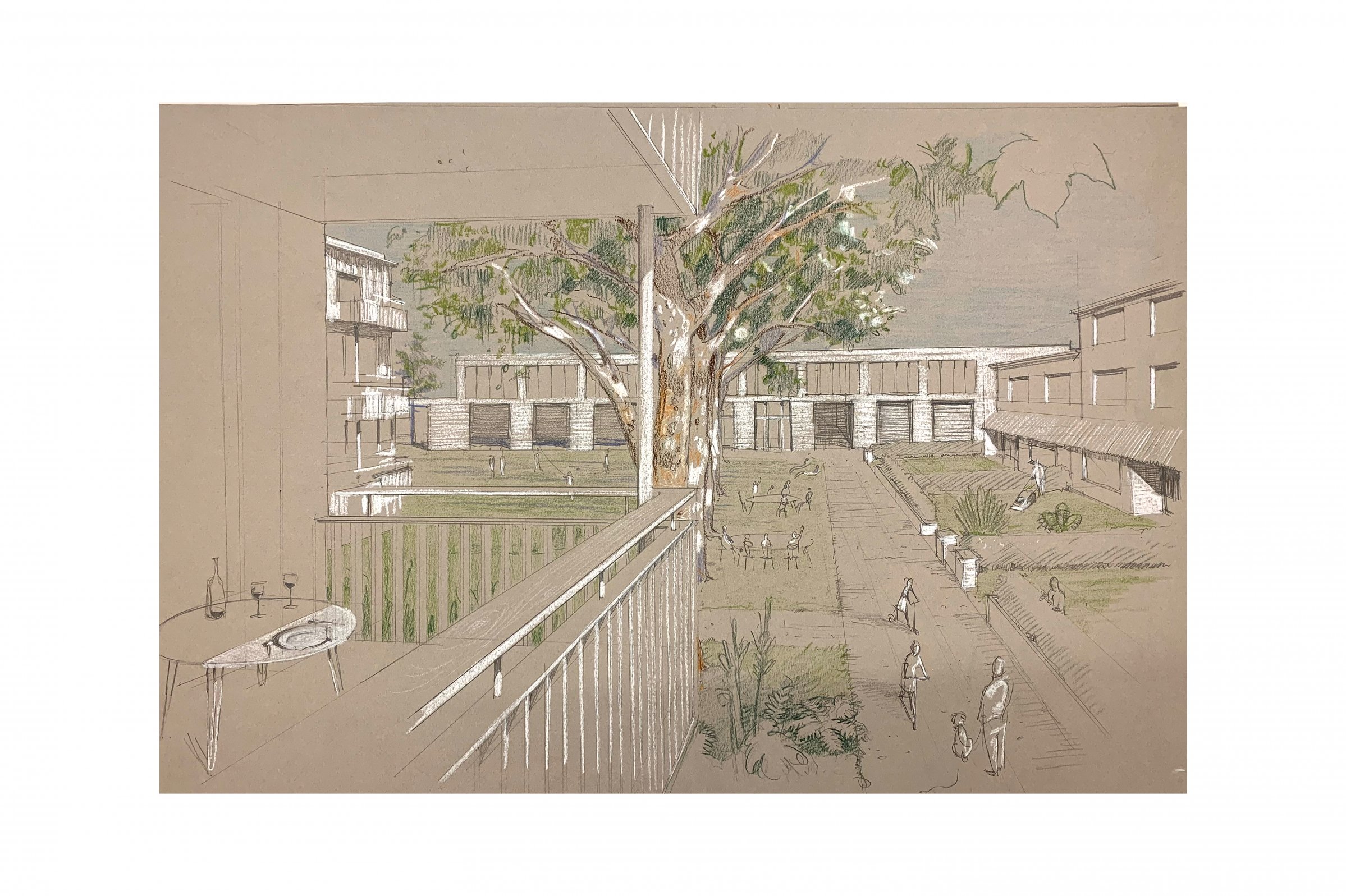

The brief on the Sint Benedictus site literally addresses these themes. In the triangular building block between Mortsel's oldest street and the railroad line , we are creating a new residential development in the inner area, like an inversion of the building block.

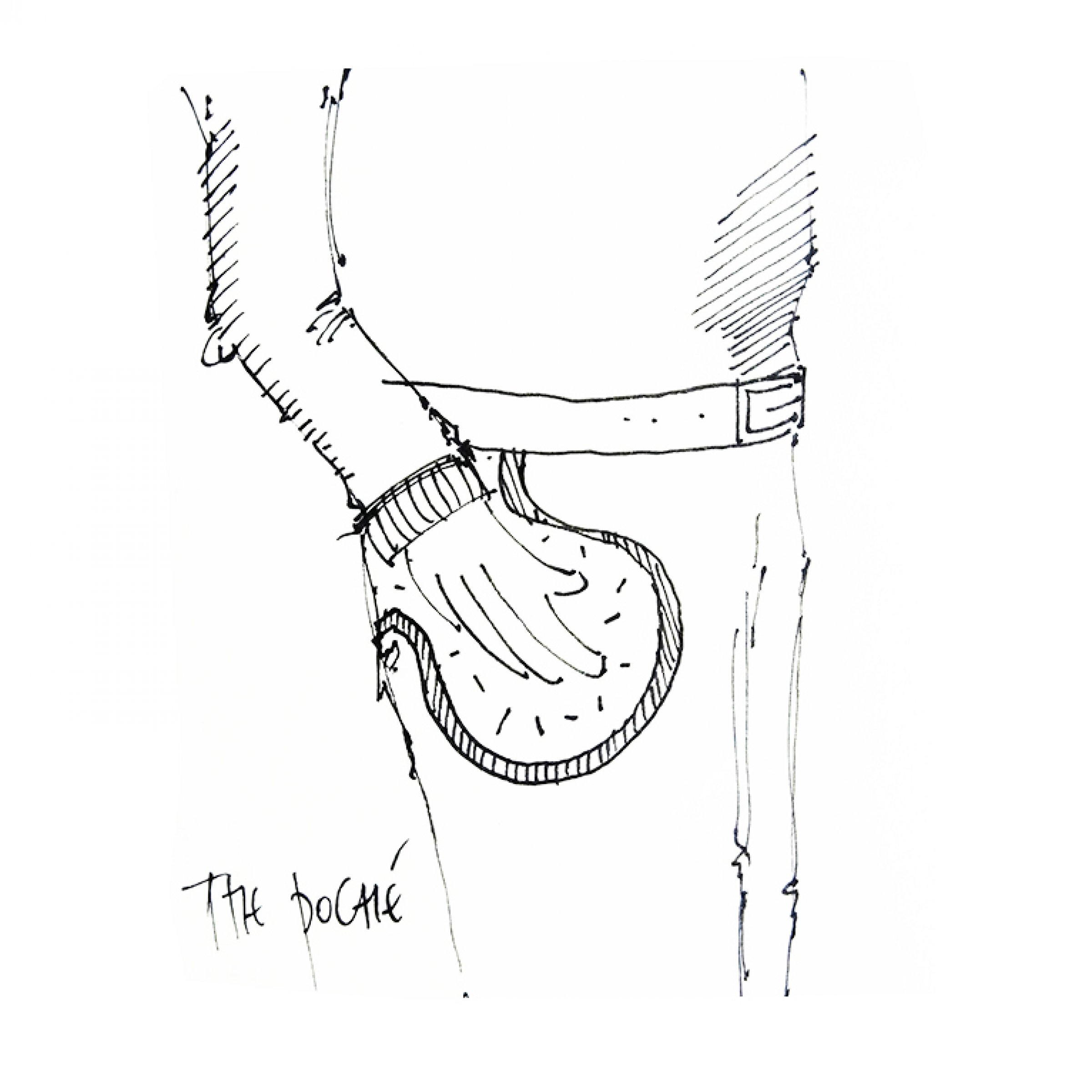

This new residential project also connects to the existing streets through relatively small openings, like a large balloon inflated by a small spout.

In this way we inevitably arrive at the idea of the poché, the fascinating in-between space at the margin, the void in the apparent fullness. A kind of secret world, an environment that belongs, yet is somehow different from the rest.

Footprint

Redeveloping this small piece of dense city, through selective demolition and densification, will therefore unequivocally commit to greenery and real public space to make the living environment a little better. It must not become a gated community, thanks to its fordable character. We employ the void as a negotiator to reconcile the urban planning figures present, a fragile exercise. In doing so, the inner area offers alternative qualities to housing, but it also contributes to the immediate environment, on which it ultimately depends.

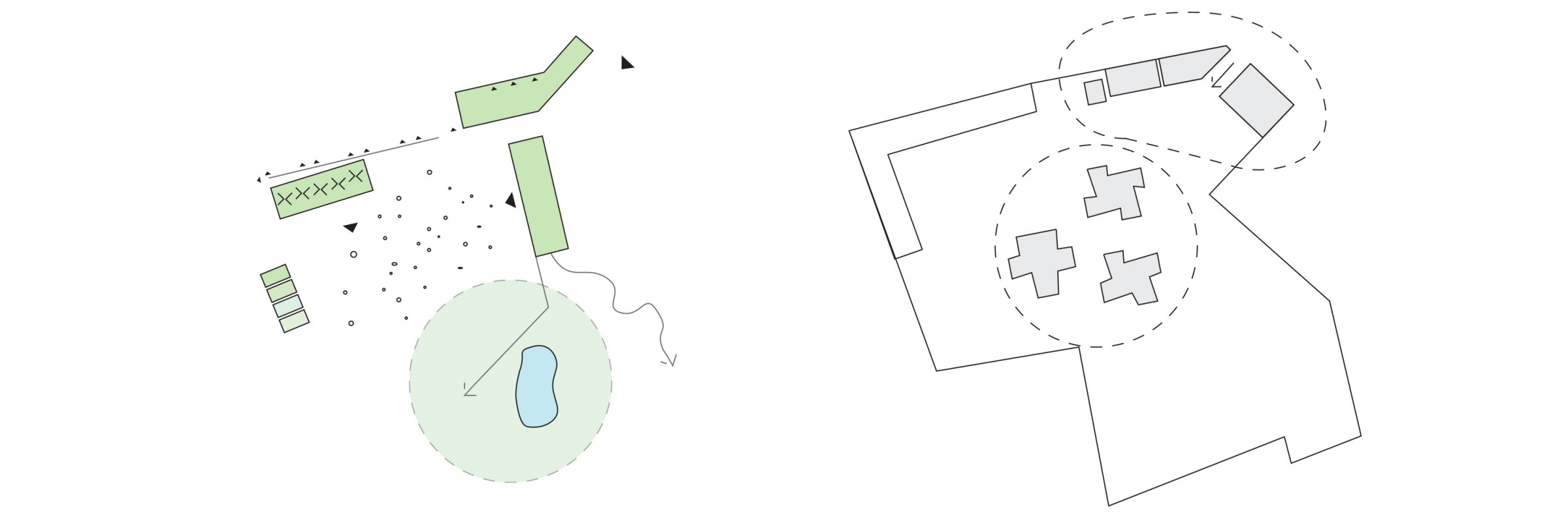

The search for what to build begins with thinking about what not to build. In doing so, we distinguish between the buildings as entrances or gateways, the houses in the edge and those in the real inner area, the forest.

The gate

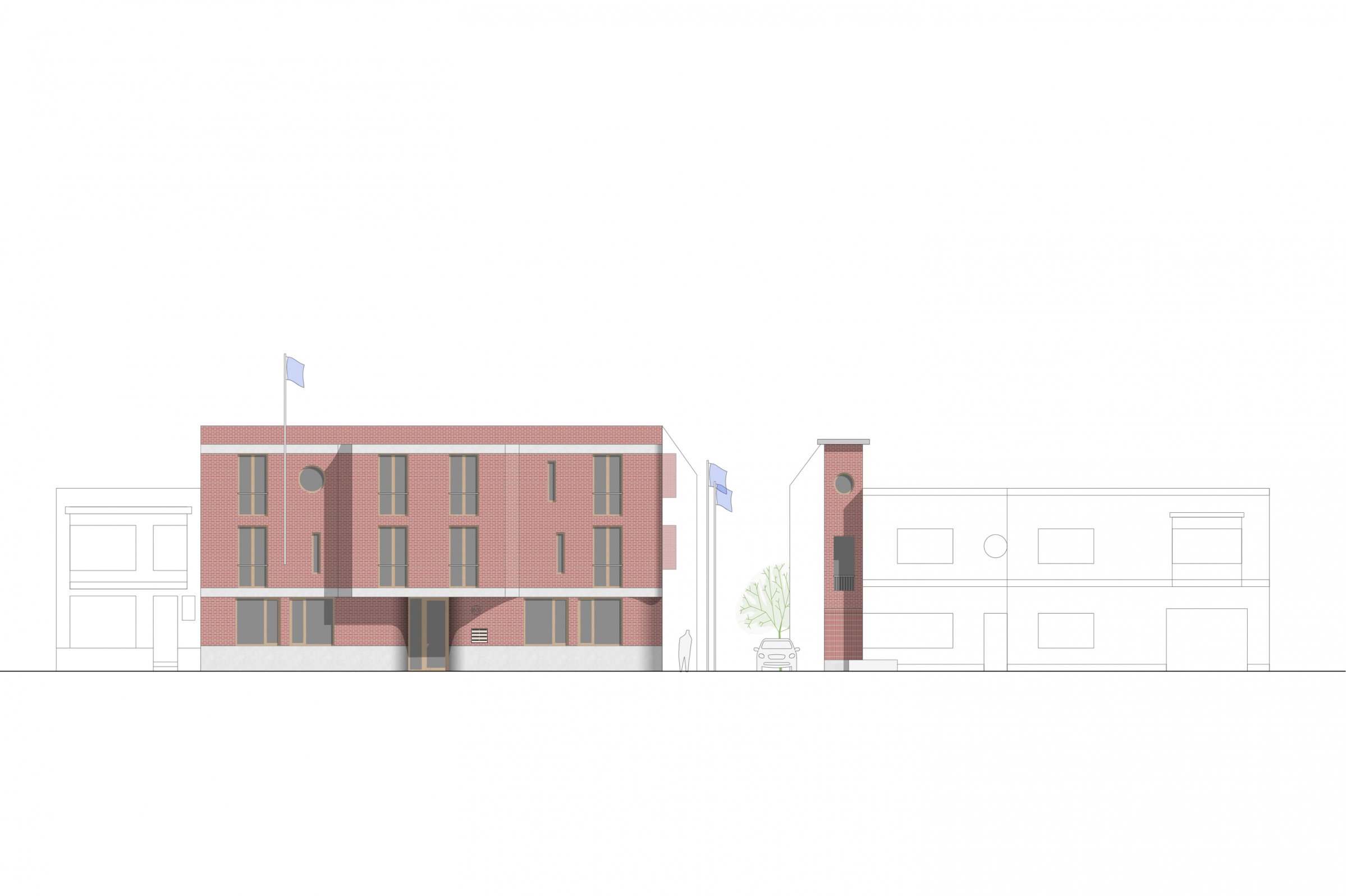

The projectstarts on the Sint Benedictus Street, where the mass of the residential street suddenly folds inward. Two strong gateway buildings (the social housing & a head building) mark the entrance to the inner area here.

The social housing units are given a clear and manageable address and the stately wedge-shaped end building embellishes the entrance to the parking lot like a porte-cochère. On top sits a large gatehouse. Belle and the Beast, one a little too narrow and the other a little too thick.

The edge

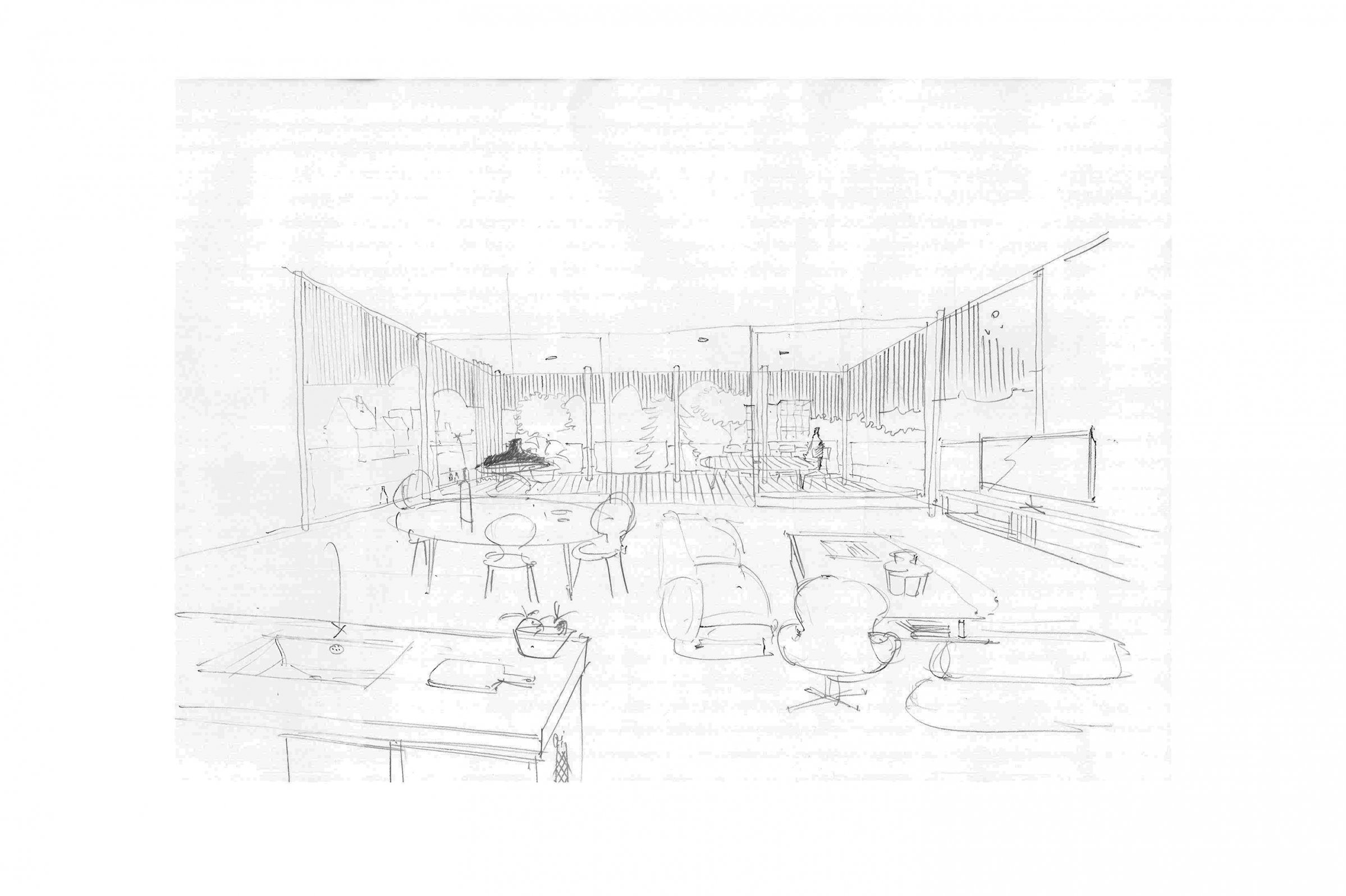

At the north and west edges, we cluster eight ground-level homes as a sheltering contour around the project area.

Two mirrored pontifical bel-etage houses stand like squires at the head of the entrance plaza, enjoying the depth view and southern sun. The former turret of the fire station concludes the series at the plaza. Yup, a folly!

The current workshops have quite a fine carcass and are, converted into beautiful ground-level homes on an alley.

A neighborhood barn, a loft, bike racks and a studio or office nestle into the existing structure like squatters, without much misgiving. The existing enclosure of the site, supplemented by a dens green screen, dampens the noise pressure from nearby train traffic.

The forest

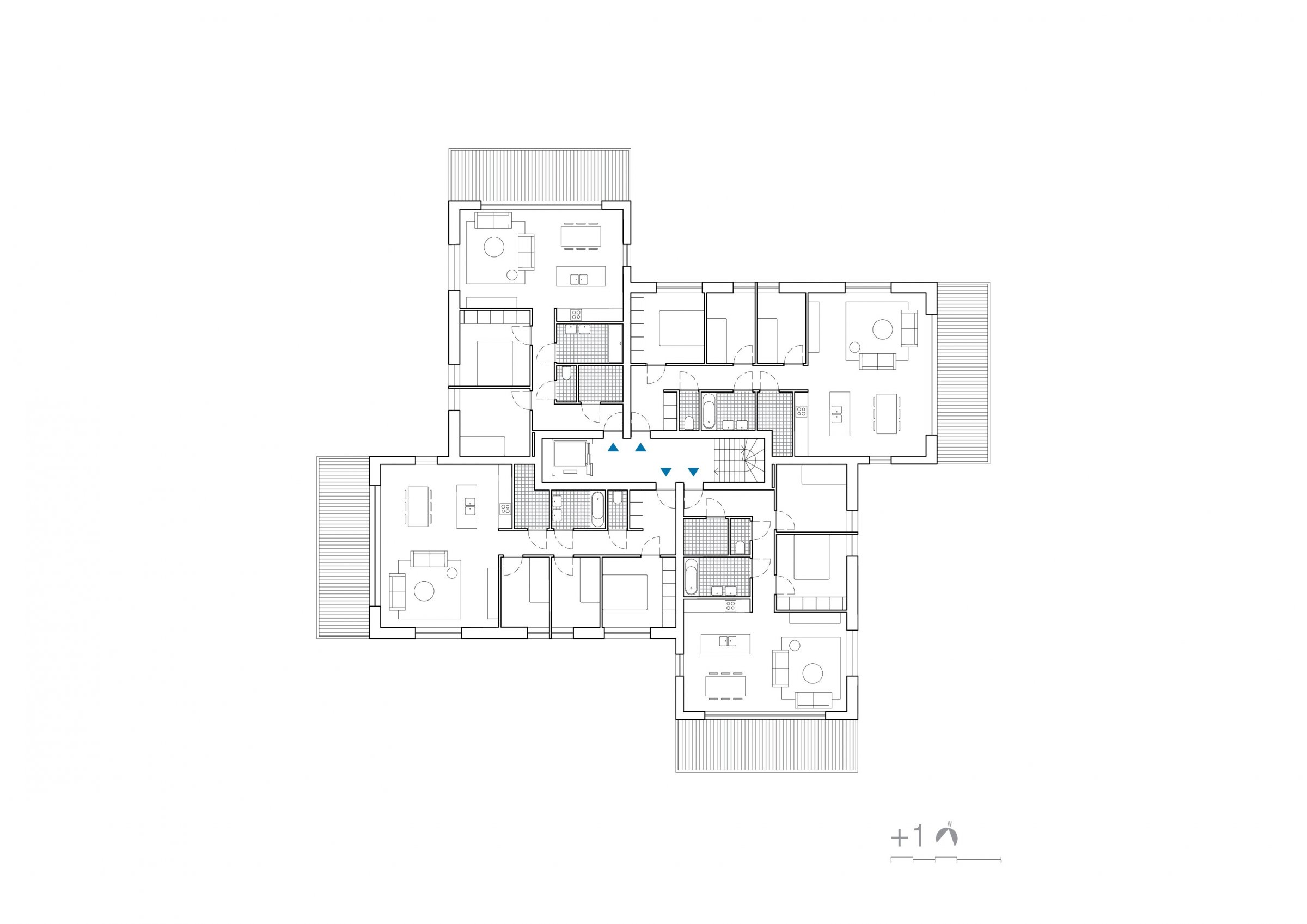

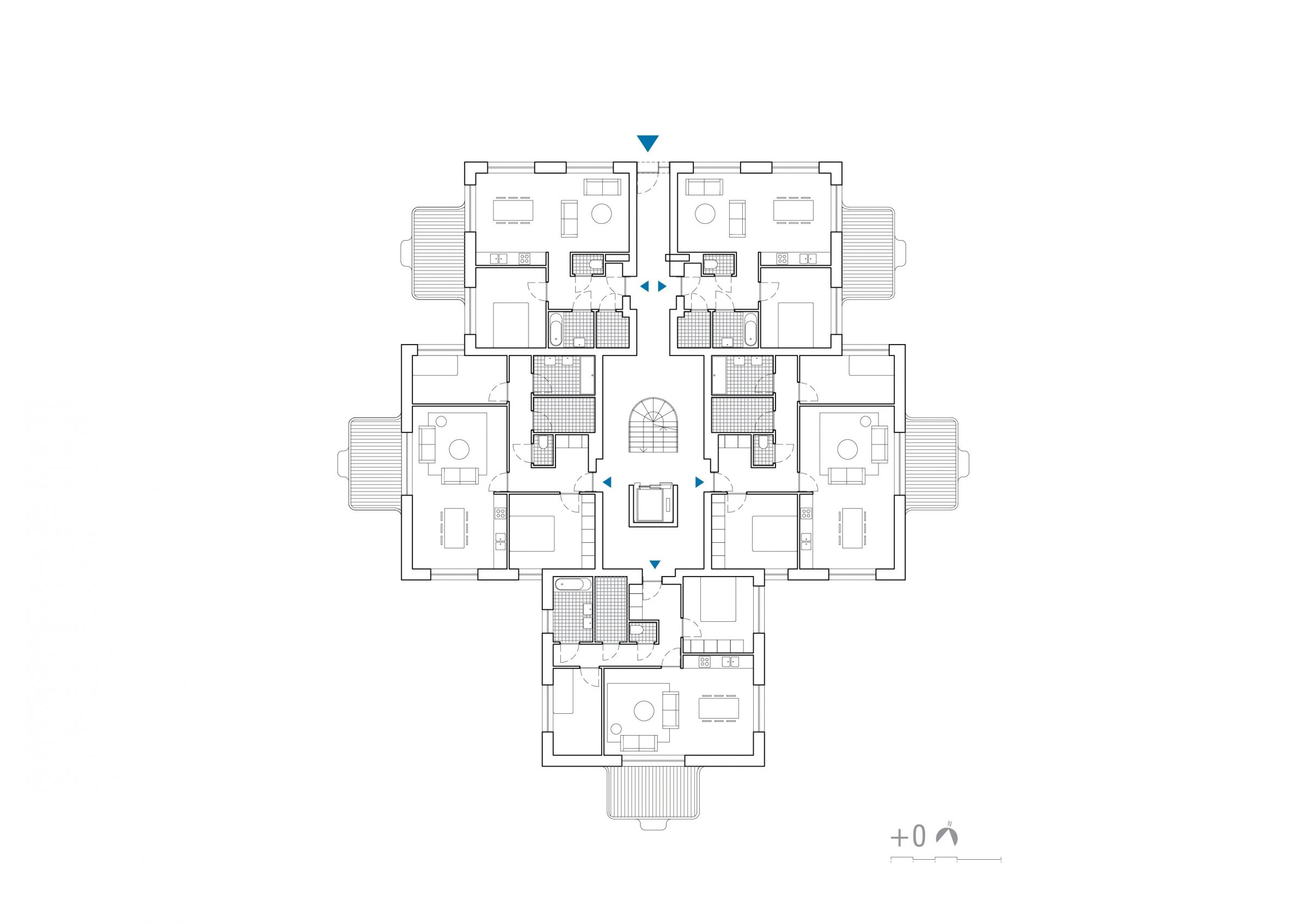

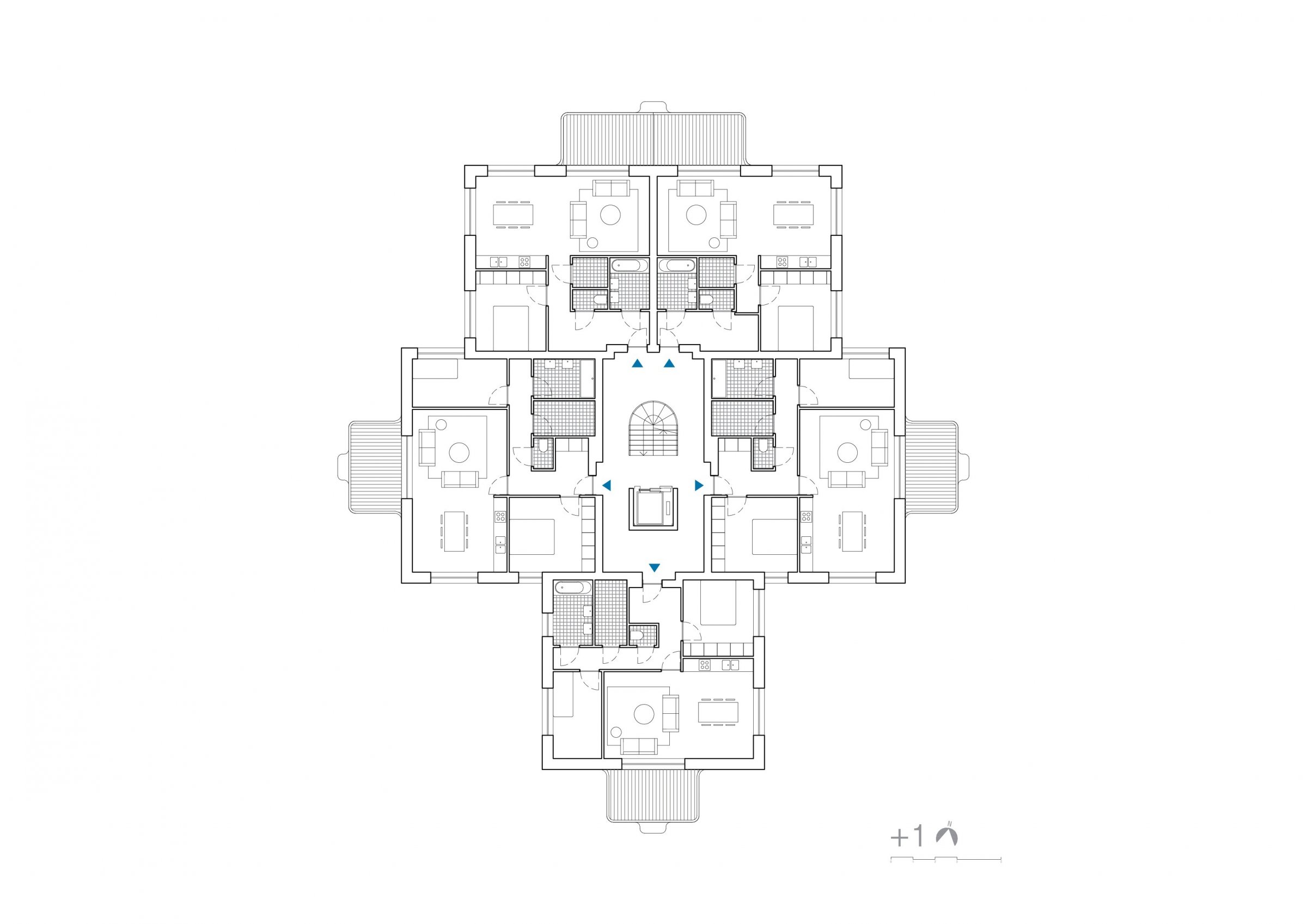

Three compact residential buildings nestle into the large green space at the core of the building block.

Two identical slimmer millwheels on the Laar and a third somewhat more compact pavilion on the plane square.

The boundary between the public domain and the private collective garden of these three residential buildings is subtly hidden in the underlayer

of the forest. By slightly raising the parking basin and retention layer in relation to the public spaces, the contacts are subtly tempered

and the building line becomes gently visible. All buildings are additionally given an haute-parterre, a slightly raised level zero, in order to buffer indoor and private outdoor spaces somewhat to the garden.